We are starving for true beauty in this world. Our yearning for satiation leads us to the plethora of shallow mimicry apparent everywhere we look, from the sameness of the mirrored behemoth skyscrapers jutting against gravity like multiple towers of babel crowding our view-line to the TikTok influencers who peddle quick-fix tricks to cover up laugh lines.

classic architecture vs modern

Since modernism entered the arena, we’ve witnessed some amazing lasting classics based on individual perspective, like Manet’s portraits or Degas’ sculptures and the beautiful renditions in the Expressionism movement, but inevitably, when moving away from order, representations will eventually dilute down to chaos and destruction. The divinely inspired becomes the ironically splattered.

Renoir/Pollock

The nihilistic movement has transformed architecture, fashion, film, and art since the late 1800s with the popularity of both Marx’s assertion that there is no overarching moral order and the only organizing principle we have to measure ourselves against is the powerful vs the oppressed and Nietzsche declaring “God is dead”. The scientific community contributed to our dissolution with the advent of the brutal theory of survival highlighted in Darwinism and Freud’s focus on instincts, perversions, and sexuality.

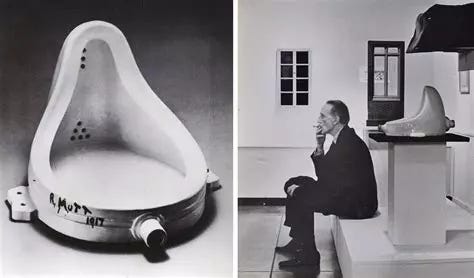

The reframing of reality outside of the divine, of course, would spawn the advent of the “truth as ugly” artistic movement with Marcel Duchamp’s, The Fountain, which, as you can see in the image below, is a urinal he bought, bolted, and signed.

Certainly, there is a place for the disillusionment, the deconstruction of the past, and the critique of the classics. Art should always reflect the artist’s perspective; however, when the totality of the art community only accepts and promotes a heavily saturated uni-theory of the world, it becomes depressing and ugly.

When we hold up the classics—the Shakespeares, the Michelangelos, the Vermeers—we see order, symmetry, and objective beauty. That’s not to say there’s no place for Warhol, Pollock, or Banksy. Questioning a system has its merit, but merely tearing it down without offering something new is not rebellion—it is regression. True artistry doesn’t just deconstruct; it builds something worthy of the transcendent.

The good modern artists do this; we wouldn’t have F. Scott Fitzgerald, Jack Kerouac or Flannery O’Conner in our literary canon if they didn’t address disillusionment with the American Dream and question our purpose — but these authors also provide hope and offer goodness as something worth striving for.

The Judeo-Christian origin story reveals God’s nature as one of order, symmetry, and magnificence. The original rebellion against this divine order began with Lucifer’s fall. It makes sense, then, that humanity continues to reenact this same pattern: rejecting God, seeking to become a god, and inevitably entering the darkness of that decision. Eventually, we reach the end of ourselves.

Conversely, the closer something mirrors divine order, the more it uplifts the mind, calms the soul, and ignites the senses. We can objectively recognize the loveliness of a clear stream trickling through a pristine forest, just as we can instinctively recoil at a mud puddle littered with abandoned gum wrappers—a scourge on that natural space. Likewise, we can watch It’s a Wonderful Life, weep at George Bailey’s awakening, and know that it offers a more profound contribution to our collective humanity than an avant-garde performance by the art world’s darling, Marina Abramović. The difference matters, and we have every right to push back.

Just because we can intellectualize a theory or theme, doesn’t make it good. Smart doesn’t always equal better. Fine art, fashion, film, and architecture have become almost super-infused with one of two aims: to protest the system—or to look inward. One is purely political, and the other is purely self-referential. In neither do we see the aim for the divine. Most modern art rejects transcendence and either embraces bleakness or chaos.

Hopefully, we are moving out of humanity’s creative adolescence and into a more mature period, one that, instead of embracing the darkness, will acknowledge it whilst still grasping towards “God's mighty hand and outstretched arm”.

Michaelangelo’s Creation of Adam

There’s a reason private schools require uniforms—they bring structure to an otherwise distracting environment. There’s a scientific explanation for why a pregnant woman feels a deep urge to “nest,” creating an ordered, loving space to welcome her baby. And it is classical music, not punk, that has been shown to create positive, intricate neural connections in brain studies.

Aesthetics shape the soul, and we must be more intentional about surrounding ourselves with beauty. The modern world’s degradation has left us spiritually fatigued—it’s time to demand more from our storytelling, music, and visual art. If, as Shakespeare said, “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players,” then let’s perform for a loving creator and collectively present something grander than ourselves.

Wonderfully stated. Poet and Catholic convert (she was an anti-Catholic atheist before a radical conversion), has a great essay that speaks to the ugliness and chaos in modern day poetry compared to the beauty and order in the classics. https://humanumreview.com/articles/god-and-the-poet

I'm giving a presentation on Catholic poetry next Tuesday, 9am, at St. Pius if you're interested.