Once upon a time, the muse was sacred. She was a goddess, a whisper from the divine, a force that ignited the greatest works of art, music, and literature. She spoke to Homer, to Dante, to Beethoven. Then, the muse began to fade. She went from celestial to flesh and blood, from mythic to mortal, and walked among us, flesh and blood —she was the infamous Patti Boyd, Eddie Sedgwick, and Zelda Fitzgerald. And now, we are on the perspicuous of the machine as muse. A synthesized echo of a once human song straining to hear God say, “Let there be light“.

From Mythic Goddesses to Modern Icons:

To examine this devolution, we begin with the original sirens of inspiration, the classical muses.

In ancient Greece, the nine muses were daughters of Zeus and the goddess of memory, (which makes the William Wordsworth line, “our birth is but a forgetting,” that much more poignant). Their daughters preceded over the following:

Calliope: Poetry

Clio: History

Euterpe: Music

Erato: Love poetry

Melpomene: Tragedy

Polyhymnia: Hymns

Terpsichore: Dance

Thalia: Comedy

Urania: Astronomy

These goddesses were the intermediaries between gods and mortals in ancient Greece’s creative and intellectual pursuits.

The Biblical Muse

Then, we have the emergence of the monotheistic God. The Sirens condensed to the breath of God — the inspiration for Song of Songs, King David’s Psalms, and the vision of the prophets. It’s the Holy Spirit in the Christian Trinity, signified by the symbol of a white dove.

The Romantic Muse

We enter the period where the breath of God is represented in the archetypical feminine guide. For these writers, BEAUTY is the door that opens us to the holy.

Beatrice Portinari: Here we have Dante’s Beatrice. Having met the real Beatrice when they were both only 9 years old. Dante idealized his first love beyond his limited interactions and placed her as the seminal muse in his La Vita Nuova and The Divine Comedy, where she serves as a symbol of the power of beauty. Beauty, according to Dante, is redeeming and can elevate us towards heaven.

Fanny Brawne: John Keats wooed his fiancé by reading her Dante’s works, she inspired many of his best-known poetry, including "Bright Star,” encapsulating their intense but tragically short affair due to Keats’ death from tuberculosis at 25. He believed beauty was the absolute. (See: Ode to A Grecian Urn).

Zelda Fitzgerald: “Beauty means the scent of roses and then the death of roses,” F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote of the romance with his tortured muse and notorious socialite, Zelda Sayre, in This Side of Paradise. While many biographers suggest that Ginevra King, Fitzgerald’s unrequited first love was the inspiration for Daisy in The Great Gatsby, it was Zelda who became the living embodiment of that elusive ”rose” and the eventual disillusionment of that dream.

Patti Boyd: What was it about this British model turned photographer and forever muse that the rock Gods of the 60s and 70s were drawn to? She had that elusive “it” girl quality — a gravitational star power that helped influence pop culture. She inspired a whopping 10 songs that we know for certain, including the classics, Something by George Harrison and Layla by Eric Clapton.

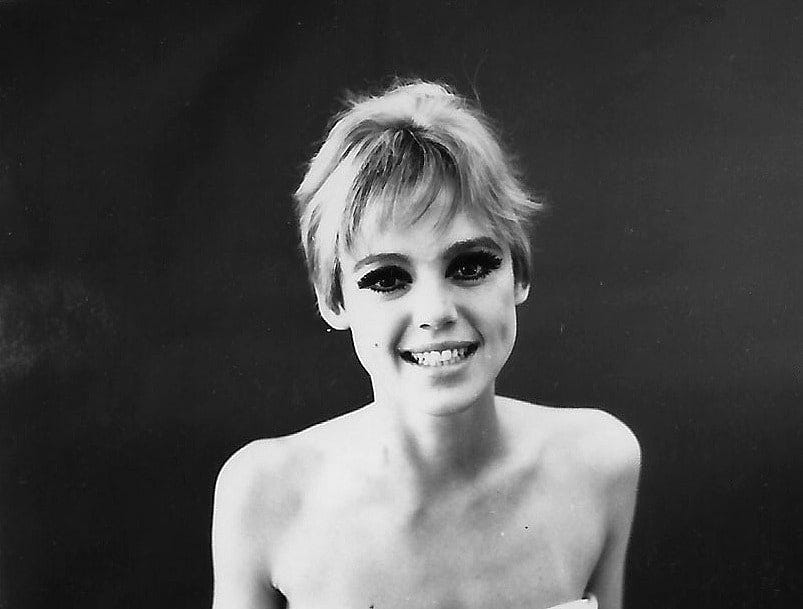

Edie Sedgwick: Andy Warhol’s tragic muse came from a highly unstable, ultra-wealthy family. She suffered mental breakdowns and was repeatedly institutionalized before heading off to New York to join Warhol’s Factory. Already grappling with a fragile sense of identity, her unpaid role as Warhol’s muse only intensified her struggles with bulimia and drug use. She appeared in 18 Factory films and inspired Bob Dylan’s songs Just Like a Woman and Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat before she retreated from the limelight and died at 28.

Sara Lowndes: Bob Dylan was married to his muse from 1965 to 1977, Lowndes inspired songs like Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands, Love Minus Zero/No Limit, and of course, Sara. “Until Sara, I thought it was just a question of time until he died. But later, I had never met a more dedicated family man.” a personal assistant once noted. Dylan frequently speaks of his eternal love for his first wife.

As writer, Elizabeth Gilbert claims in her book, Big Magic, “muses come and go. Sometimes the voodoo will hit, and you will find yourself in a creative trance.”

That may be true if not fixated on an ordered love, as we can see from the tragic consequences of artists who place too much pressure on their earthly muses Fitzgerald famously stated, “Zelda's the only God I have left now”.

While earthly beauty can be a doorway that unlocks something akin to a heavenly light, it will only be a murky reflection if the artist’s goal isn’t fixated on the divine. The muse becomes an illusion. It’s the green light that Jay Gatsby so desperately tries to reach.

And what happens when inspiration is not even flesh-and-blood but synthetic as more people turn to AI? There is a death of true creativity when the muse is severed from the ultimate creator.

If our North Star is fixed on beauty, truth, and goodness, we can continue creating lasting works of art—like Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, Handel’s Messiah, and Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. Of course, we will always fall short of these greats who achieved the seemingly impossible—art that transcends time. But when we inevitably falter, exalting romantic love on our arduous climb toward heaven, it can offer a moment of reprieve along the way, and we can honor these muses without allowing them to overshadow our ultimate pursuit.

Thank you :)

Fascinating! TY Valerie for pulling all these ideas together. I’ll be thinking about how I’m inspired and by who.